A troupe of “foreign artists”

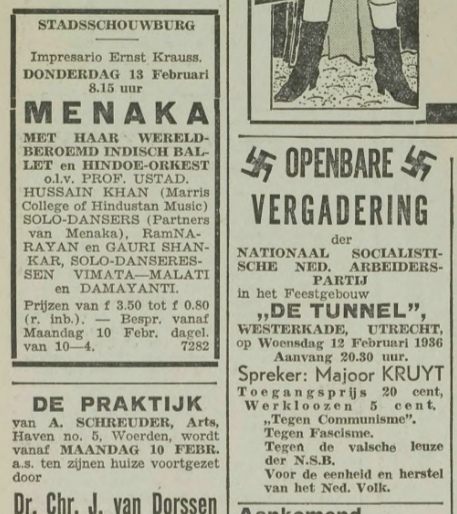

In February 1936, the Menaka Ballet began an intensive tour in The Netherlands. The dancers and musicians performed in larger cities as well as in smaller towns. On February 8, 1936 newspaper Utrechts Nieuwsblad carried an advertisement for the performance in the Stadsschouwburg of Utrecht. The small ad in the first column of the last page doesn’t immediately stand out.

In the second column, somewhat lower than the advertisement for Menaka, a the announcement of a public meeting (“openbare vergadering”) catches the eye. It is a call to visit attend a public meeting of the Nationaal-Socialistische Nederlandsche Arbeiders Partij (National-Socialist Dutch Workers‘ Party, NSNAP). The NSNAP was a splinter party of the Nationaal Socialistische Beweging in Nederland (Dutch National Socialist Movement – NSB). Differences of opinion and ruthless competition had led to three splinter parties with the name NSNAP. The meeting in Utrecht was of the NSNAP led by C.J.A Kruyt (1869-1945); a faction with virulent and violent antisemitism at its core. [1]

Kruyt was a former major in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army, the military force for the former colony in Southeast Asia. One of the founding principles of the NSNAP-Kruyt was that the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies should first and foremost act in the interest of the colonized people: “not capitalist exploitation, but national socialist natural development. […] Production in pursuit of great profits, ignoring the interests of the native population, has led the rich Indies to a state of decline and poverty.” [2]

In stark contrast were the views on the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean, with a population that descended of indigenous inhabitants, enslaved Africans and indentured labourers from China, Java and India. According to NSNAP-Kruyt ‚this this had led to “strong degeneration”, the proposed solution was exportation of the inhabitants, in order to replace them with ethnic Dutch. [3]

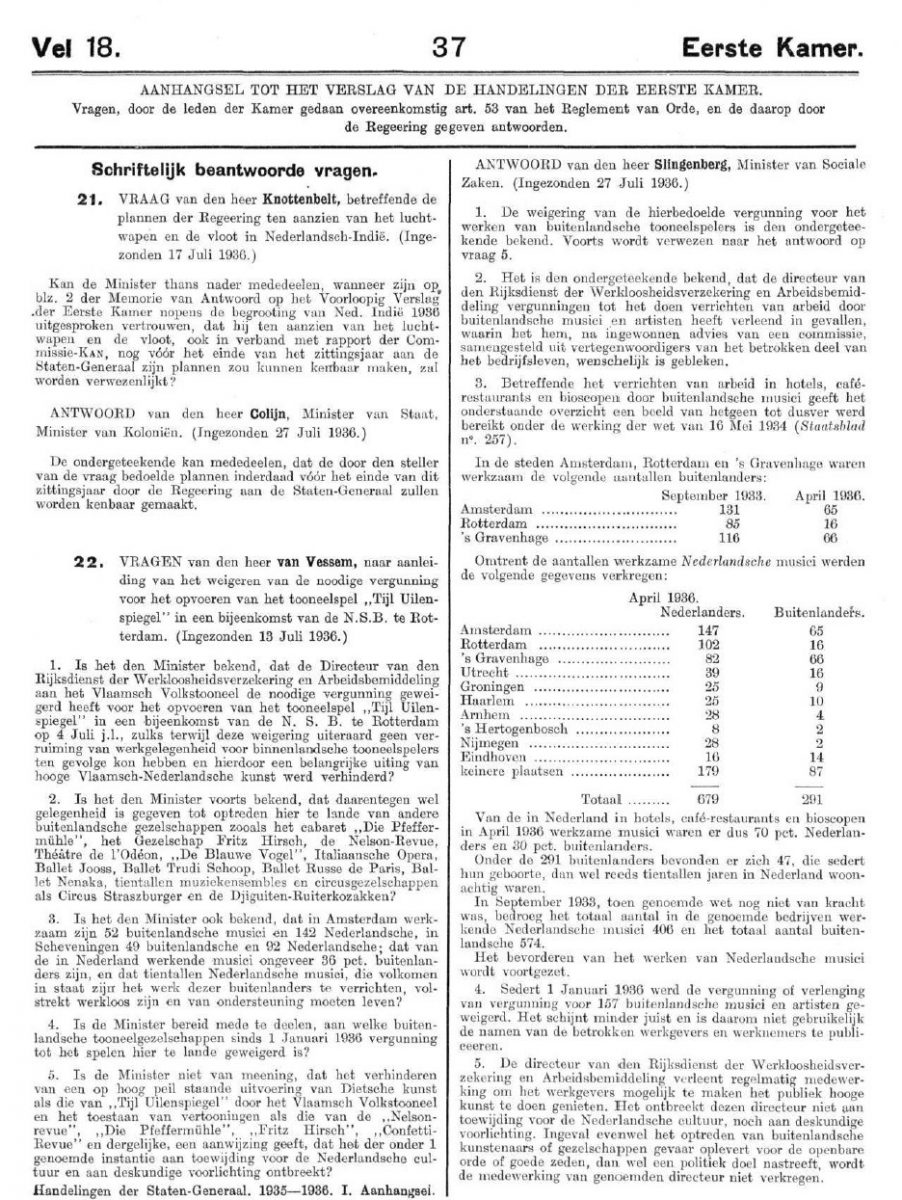

Whereas the NSNAP remained a marginalized minority, the NSB had been elected into the Senate (Eerste Kamer) of the Dutch Parliament (Staten Generaal) in 1935. Member of parliament Anton van Vessem (1887-1966) mentioned the Menaka Ballet in a series of questions directed at the Minister of Social Affairs. [4] Van Vessem complained about the treatment of a Flemish actor who would perform “Till Eulenspiegel” at a gathering of the NSB in Rotterdam. Since the actor was refused a work permit for The Netherlands, the public was withheld of an expression of “high Flemish-Dutch art”.

He condemned the fact other „foreign companies“ did receive a permit to tour in The Netherlands. The tours of the Ballet Russe de Paris, Ballet Trudi Schoop and Menaka Ballet signalled, in the eyes of Van Vessem, a “lack of dedication to Dutch culture.” The Menaka Ballet was the only extra-European artist on the list of the politician. Van Vessem reminded the Minister of Social Affairs that while “foreign artists” were active in the country, Dutch musicians who were “completely capable to do the work of the foreigners, were unemployed and living on benefits.” [5]

Van Vessem listed several artists, although he did not explicitly mention they were Jewish: Circus Strassburger, the Nelson-Revue, [6] and Operetta Fritz Hirsch. Fritz Hirsch (1888-1942) had been active in The Netherlands since 1926, and had met enormous success . In then years his company had performed 52 different operetta’s, some productions were staged over a hundred times. [7] Hence, the questions in parliament could be regarded as a thinly veiled antisemitic attack. Other performances the Dutch politician questioned had openly opposed national socialism: Erika Mann’s anti-nazi cabaret Die Pfeffermühle [8] , and the ballet of Kurt Jooss, who in 1933 fled from Germany to The Netherlands after his refusal to dismiss Jewish dancers from his company. [9]

References

[1] Willy Sjoerd Huberts, In de ban van een beter verleden: Het Nederlandse fascisme 1923-1945 (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen 2017) 155. https://pure.rug.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/39255821/Chapter_3_.pdf

[2] Beginselen van de Nationaal-Socialistische Nederlandsche Arbeiders Partij

https://www.historici.nl/pdf/kpp/illustraties/nationaal_socialistische_nederlandsche_arbeiderspartij/programma2.pdf

[3] idem.

[4] ‚Aanhangsel tot het verslag van de handelingen der Eerste Kamer‘, 27-07-1936, Officiële bekendmakingen, https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/0000059098

[5] idem.

[6] Malte Gasche, ‚Carl Strassburger (1899-1953) – From a Boycotted “Jewish Circus” to a Successful Dutch Company‘, Diverging Fates – travelling circus people in Europe during national socialism (October 29, 2018). http://www.divergingfates.eu/index.php/2018/10/29/carl-strassburger-1899-1953-from-a-boycotted-jewish-circus-to-a-successful-dutch-company/ ; https://theaterencyclopedie.nl/wiki/Rudolf_Nelson_Revue.

[7] https://theaterencyclopedie.nl/wiki/Fritz_Hirsch_Operette.

[8] Helga Keiser-Hayne, Kabarett „Die Pfeffermühle“, 1933-1937, publiziert am 11.05.2006; in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns, URL: <https://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/Lexikon/Kabarett_“Die_Pfeffermühle“,_1933-1937> (05.04.2021)

[9] Caroline Cox.’ Dance in Nazi Germany’, Washington College Review, XXV (2018) https://washcollreview.com/2018/07/16/dance-in-nazi-germany/