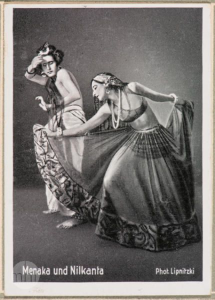

This article was published first by Parveen Kanhai on April 23rd, 2020 on her blog Toen t zien. (http://www.toentezien.nl/uncategorized/1931-1932-menaka-nilkanta/). Parveen regularly writes about the colonial production of otherness by examining the different presentations of humans in colonial exhibitions, circuses or human zoos. For this purpose she studies all forms of images, photographs, advertisements and newspaper reports that are publicly available in digital archives. Parveen researched the first appearance of Menaka in Europe from 1931-1932 with her then dance partner Nilkanta and thus closes a huge gap in the Menaka-Archive. Ernst Krauss’s estate contains only a few references to Menaka’s performances in the Netherlands in 1931 – including an entry in Krauss’s guest book. In the Dutch press Parveen has identified a number of Menaka performances and the repertoire performed. Using Menaka interview statements, she contextualizes Menaka’s dance project between the field of protonational reforms in India and colonial productivity in Europe. The 1931 Menaka performances in the Netherlands can thus be read as a prototype for the 1936-38 tour.

1931-1932 Menaka & Nilkanta

This blog post is inspired by the Menaka Archive. Launched in November 2019, the archive presents the findings of four years of research into the European tour of the Indian ‚Menaka Ballet‘ from 1936-1938. The Menaka Archive has a very rich database, including primary sources and a meticulous list of tour dates. Whilst the website is aimed at dancers and musicians in Germany and India, I attempt to make a small contribution by using Delpher, the Dutch database for digitized books, newspapers, and magazines. I will focus on Menaka’s first Dutch performances in 1931.

In the French database ‘Retronews’ the first European performance I could find was on November 7, 1930 in the Salle Pleyel, Paris. Menaka was accompanied by her dance partner Nilkanta and singer Bina Addy. 1 In March several Dutch newspaper reported that Menaka was ‘persuaded’ to perform in The Netherlands after successful shows in Paris and Berlin. 2

1931-1932 Menaka in The Netherlands, based on announcements in Delpher.

18 March 1931 Amsterdam Stadsschouwburg

23 March 1931 Haarlem Stadsschouwburg

24 March 1931 The Hague Diligentia8 April 1931 The Hague Diligentia

5-6 June 1932 The Hague Indische Tentoonstelling

Reporters of two national newspapers, De Telegraaf 3 and De Tijd, 4 interviewed Menaka and Nilkanta. Both journalists quoted Menaka when she shared her views on the state of dance in her home country. Her remarks can be examined in the wider context of fundamental shifts in Indian dance, during the 1920s-1930s.

‘Uncivilised demeanour’

Menaka: […] In India dance is at a very low level. The same dances are performed in the temple and general gatherings, but the performers are women of uncivilised demeanour. There is no difference between general dances and religious dances, the dances in the temple are not religious. […] 5

Menaka , the stage name of Leila Sokhey (née Roy) hailed from Calcutta, where she belonged to a Brahmin family. As a child, she saw many performances of professional dancers 6, in the above quote she referred to them as ‘women of uncivilised demeanour’. Until the twentieth century, dancers in India belonged to specific, artistic communities. Women of these communities received extensive training in dance, literature, music and singing from childhood onwards. In North India the professional artistes were attached to predominantly Muslim courts, with cities like Lucknow and Jaipur, among others, as reputable artistic centres.

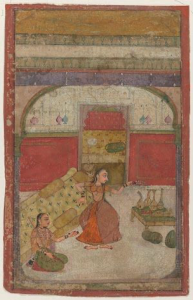

Rajasthan in North India was ruled by Hindu Rajputs, but they were influenced by the Indo-Persian culture of the Mughal imperial court.

In this drawing the dancer at a Rajasthani court has her feet turned out and knees bend, around her ankles she wears noopur or dancing bells.

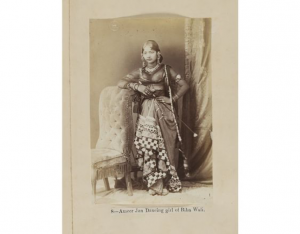

The British Raj (1858-1949) , or direct rule in India, disempowered local kingdoms. A significant number of dancers and musicians across North India left regional courts and migrated to the city Calcutta, the new administrative capital. Here the art of the hereditary dancers became reliant on the patronage of men from the wealthy, upper-classes. 7

Menaka’s negative appraisal of the dance artistes reflect the sentiment of the anti-nautch movement that spanned from the early 1890s to the 1930s. ‘Nautch’, is an Anglicized form of the Hindi word for dance, naach.

There is a large body of literature that is concerned with the anti-nautch movement and the subsequent transformation of dance.8 Amrit Srinivasan was one of the first to discuss this campaign against hereditary dancers in the context of social reform movements of the late nineteenth century.

Pressure groups, associations and lobbies of educated Hindus served in that period as a platform to respond to critiques brought forward by British missionaries and legislators. In doing so, Hindu reformers defined the hereditary dancers in Victorian terms. 9 Compared to other women, dancers possessed a degree of agency: they were very well versed in the arts, literate, and had non-marital relationships with men: their patrons from the upper strata of society. Due to these non-conjugal, sexual relationships hereditary dancers were criminalized as morally inferior ‘prostitutes’. 10

Displacement

As a result of complex changes in the moral, political and judicial realm, the hereditary artistes were removed from the dance and replaced by women from the upper castes, deemed worthy to perform the art. 11

Menaka broached this subject in the interviews:

[…] When Pavlova 12 saw me dance in my family circle, where I often danced, she said to me: “why don’t you dance and do something with your life. You can be of value for your people.” This entailed grave difficulties before I could even begin, I had to convince my husband, then my family and eventually all people from my caste. In 1927 I gave my first dance recital in Bombay, to a shocked and indignant audience. However, the second time I received much approval and I received many letters from girls of my class who wished to receive formal dance training . 13

While recognizing the manifold factors that contributed to the displacement of hereditary dancers from the art, Natarajan mentions the personal interest of Brahmin women like Menaka who took to dancing. In their struggle to overcome caste barriers, their priority was legitimizing their own public appearances. The plight of the hereditary dancers, or seeking avenues where they could pursue their profession, was hardly a concern. 14

‘Priestess of dance’

[…] Meanwhile she chatters about famous Indians like Tagore and Gandhi. She tells us how she as well is bothered by the fact that India isn’t purely Eastern anymore. Despite her European orientation […] she wants to devote herself with all her might to save the pure Indian dance. […] “Menaka was the priestess of the all-knowing deity Indra, I want to be the priestess of Hindu dance”. 15

Leila Sokhey was born into the so called bhadralok¸ the upper and middle classes of Bengal who articulated a sense of nationalism., with members of the Tagore family as preeminent intellectuals. Their nationalist construction of the Indian identity revolved around a distinct Hindu spirituality, which was embedded in ancient traditions and scriptures. While hereditary dancers were considered degraded, the art itself was conceived of as a sacred heritage, an embodiment of devotion, untouched by Islamic or European culture. 16

[…] What I mean with my movement for dance in India is a reconstruction of the ancient dance. For this I have found material with teachers who have taught dance from generation upon generation. However, they taught only in the technical sense; the spirit was completely lost. […] 17

In this quote Menaka makes it clear her teachers were the men from the hereditary artist communities. Although masters of music and movement, they did not embody the ‘pure’ dance:

[…] I had to start from scratch. […] One sees in statues and reliefs that ancient Hindus must have had an extraordinary technique. […] I do think Balinese dance embodies Hindu dance in its purest form. 18

The performance in The Hague in March was tremendously successful, Menaka and Nilkanta were invited again to the theatre for one evening in April 1931. In 1932 they performed two days during the ‘Indische Tentoonstelling’, a colonial exhibition in The Hague. According to newspaper ‘Het vaderland’ the dance couple was preparing their journey to India, since Nilkanta had to return because of family circumstances. Despite the fact that the Dutch Indies were the focal point of the exhibition, Het Vaderland mentioned Menaka and Nilkanta agreed to end their European performance here because of the ‘Indian atmosphere.’ 19 In 1936 Menaka would return to The Netherlands for a far more extensive tour.

Dances performed in 1931

- Panghat Nritya dance on the shore of the Jamuna

- Ushas dance of the goddess of dawn

- Ranga Lila dance of spring

- Yuddha Vidaya the wife of the warrior

- Bhakti Bhava dance of devotion

- Naga Kanya dance of the snake princess

- Lakshmi Darshan birth of the goddess Lakshmi

- Amaravati Nritya based of the buddhist sculptures of Amaravati

- Gramya Goshthi the well of the village

- Taraneh Usstragh Mongolian serenade

Source: Het Vaderland, 16-03-1931 and 19-03-31.

1. https://www.retronews.fr/journal/l-intransigeant/2-novembre-1930/44/909025/6 l ↩

2. ‘De Hindoe-danseres Menaka’, De Haagsche Courant, 06-03- 1931↩

3. ‚De Hindoe-danseres Menaka. De renaissance van den dans in Indië – Invloed van Pawlowa‘, De Telegraaf (17-03-1931). ↩

4. Caty Verbeek, ‘Menaka. “Ik tracht de Indische volksziel te brengen”’, De Tijd (05-04-1931). ↩

5. De dans in Indië staat op een zeer laag peil. zegt Menaka. In de tempels worden dezelfde dansen gedanst als in de gewone samenkomsten, doch ze worden beoefend door vrouwen van onbeschaafde allures. Onderscheid tusschen religieuzen dans en gewone dansen bestaat er niet en u moet zich die dansen in den tempel of bij den tempel ook niet als religieuze dansen denken. […] ‚De Hindoe-danseres Menaka’, De Telegraaf (17-03-1931). ↩

6. Margaret E. Walker, India’s Kathak dance in historical perspective (Surrey 2014) 18. ↩

7. Pallabi Chakravorty, ‘Dancing into modernity: multiple narratives of India’s Kathak dance’, Dance Research Journal 38/ 1&2 (2006) 115-136, 117. ↩

8. The anti-nautch movement was particularly strong in South India, for an overview of the historiography see: Davesh Soneji, Unfinished gestures. Devadasis, memory, and morality in South India (Chicago 2012) 4-14. ↩

9. Amrit Srinivasan, Reform or Conformity. Temple ‚prostitution‘ and the community in Madras Presidency‘, in: Bina Agarwal, Structures of patriarchy: the state, the community and the household (Delhi 1988) 176-198. Retrieved from: http://acceleratedmotion.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/reform_conformity.pdf ↩

10. Soneji, Unfinished gestures, 3. ↩

11. Srividya Natarajan, Another stage in the life of the nation: sadir, bharatanatyam, feminist theory (Dissertation, University of Hyderabad 1997) 172- 173. Retrieved from: http://igmlnet.uohyd.ac.in:8000/hi-res/hcu_images/TH2252.pdf↩

12. Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova (1881-1931) visited India in 1922 and 1928-1929. ↩

13. […] “Toen Pawlowa mij dansen zag in den kring mijner familie — want ik danste veel — zeide zij tegen mij; waarom dans je niet en waarom doe je niets in je leven. Je kunt iets voor je volk doen. En het had ontzettend veel moeilijkheden ten gevolge, alvorens ik er mee beginnen kon, toen mijn man overwonnen was kwam de familie en vervolgens alle menschen van mijn kaste. In 1927 danste Ik voor de eerste maal in Bombay en de menschen waren geïndigneerd en verslagen. Maar den tweeden keer vond iedereen het prachtig en kreeg ik vele brieven van meisjes uit mijn stand die onderricht wenschten […] ‚De Hindoe-danseres Menaka’, De Telegraaf (17-03-1931). ↩

14. Natarajan, Another stage in the life of the nation, 167. ↩

15. […] Ondertusschen babbelt Menaka nog over bekende Indiërs, zooals Tagore en Gandhi. Zij vertelt, hoe het ook háár hindert dat Indië niet meer zuiver Oostersch is en hoe, ondanks het feit dat zij Europees georiënteerd is […] zij al haar krachten wil inspannen, voor Indië den zuiver Indischen dans te redden.’ Caty Verbeek, ‚Menaka‘ , De Tijd (05-04-1931). ↩

16. Nilanjana Bhattacharjya, ‚A productive distance from the nation: Uday Shankar and the defining of Indian modern dance‘, South Asian History and Culture 2/4 (2011), 482 -501, 483-484. ↩

17. […] Wat ik met mijn mouvement ten gunste van den dans in ons Indië bedoel is een reconstructie van de oude dansen, materiaal daarvoor vond ik bij de onderwijzers die de dansen van generatie op generatie overbrachten, dat wil zeggen alleen in technischen zin; de geest ging volkomen verloren. […] ‚De Hindoe-danseres Menaka’, De Telegraaf (17-03-1931). ↩

18. […] ik moest van den grond af aan beginnen Men ziet in de statuen en reliëfs dat de oude Hindoes een buitengewone techniek gehad moeten hebben. Ik meen echter dat de dansen van Bali de Hindoedansen zijn in den puursten vorm. […] ‚De Hindoe-danseres Menaka’, De Telegraaf (17-03-1931). ↩

19. ‘Indische Tentoonstelling’, Het Vaderland (5-06-1932. ↩